“Hello friends!”

When you read those words, imagine hearing them in a sweet, feminine, sing-song voice, the kind you’d associate with a Kindergarten teacher, or elementary school librarian. Now picture yourself at six years-old, the age of most Kindergarten students. What does your six year-old self imagine comes next, in that lilting tone?

I’m going to go out on a limb and guess it’s not that your skin color is the most important thing about you, that being white is a “bad deal,” that being black puts you in constant danger from white people, and that “whiteness,” itself is “a pact with the devil.”

But that’s what the children in 36 public school districts in 15 states are hearing when their teachers and librarians read them the book Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness, by Anastasia Higgenbotham. Here’s a video of a Dad (who supports it) reading it aloud on YouTube (his description, and invitation to children directly, is pictured below):

The book, which opens with the quote pictured below, from Toni Morrison, is colorfully illustrated using collages, and written in the author’s own handwriting.

Right away, there’s the claim that white supremacy is the default state of affairs wherever white people are, and it’s the job of white people (including white children in the class) to “dismantle” it.

Do these children understand what “white supremacy is?” Elementary school kids have not yet been taught the history of this or any other country, nor do they read proficiently enough to learn about it on their own. In addition, elementary-aged students have not yet developed their capacity for complex thinking and reasoning.

According to Ken Ginsburg, writing about The Teen Brain for the Center for Parent & Teen Communication:

“Young children through the ages of approximately 11 or 12 tend to think in concrete ways. This means they see things as they are. They do not look far into the future, imagine nuance, or grasp complex motivations that sometimes drive behavior.”

So it’s safe to say at this stage of their education, everything the typical kid in grades K-5 knows about race they’ve been told by their teachers or parents, and they’ve had no reason to question either. They see things “as they are,” and if they aren’t seeing it themselves, they believe what they’re told. Remember, this is the age when kids still believe in Santa and the Tooth Fairy, so believing the Devil made a special pact with “white people” isn’t so far-fetched.

It’s important to remember that kids are new to this thing called life, never mind to the process of formal learning. They won’t even be developmentally ready to integrate complex ideas and concepts, like “white supremacy,” or “racism” until they’re 11-12 years-old, so roughly sixth grade. Even then, skepticism and critical thinking must be taught. These habits-of-mind don’t come naturally, and presenting opinions as facts is a good way to prevent them from developing at all.

Other examples of opinions presented as fact are explicit in these lines from the book:

“Racism is a white person’s problem, and we are all caught up in it.”

White adults “want to bury the truth.”

“Deep down we all know color matters.”

“Skin color makes a difference in how the world sees you, and how you see the world.”

“It makes a difference in how much trouble seems to find you, or let you be.”

“Your skin color affects the most ordinary daily experiences.”

Children are told it will “take courage” to face “the truth,” and then “especially a painful truth about your own people.”

Whose people? The student is led to believe “white people” are a “people,” a cohesive group, collectively responsible for the worst actions of some, or more bizarrely, of those long dead. Strangely, only white people are tainted with this collective guilt, and children are given the impression there is no way to be racist if you do not have white skin. There are no references whatsoever to “racism” that don’t stem from “whiteness” which the illustrations make clear is attached to phenotypically white skin.

Students are even led to believe a perfectly rational decision, like making sure your car doors are locked when driving through a dangerous neighborhood, is inherently racist. But notice the white hand, as if a black adult would never do the same thing. Adding to the negative implications of this behavior is the claim that people doing this “think they are the good ones.”

How does the author know? Maybe the driver thinks they are the vulnerable ones? Maybe it’s a woman driving, and she’s afraid of bigger, stronger men she sees on the sidewalks. What if there have been carjackings in the area? Is this behavior such a clear-cut sign of racism, never mind specifically “white supremacy” that it should be singled out in a picture book for young children?

What’s the point of this anyway? Are children supposed to watch their parents like hawks, and call this out as “racist?” Even if we give the author her argument, and treat door-locking as clear evidence of racism, is deputizing young children to police their parents an appropriate thing for public school teachers to do?

Credit where it’s due, the book does go on to suggest the children use their curiosity to learn more about racism, but keep in mind the text is aimed at very young, pre-literate children. How much extra reading are they likely to be able to do now? At school, aren’t they still at the mercy of their teachers and the librarian? Won’t most of their questions get answered by the same people who chose this book in the first place? How likely are they to encounter different opinions among the adults at school? If the only challenge they hear to these opinions comes from their parents, are they ready to emotionally handle choosing between them and their teachers?

The book then leaps directly from telling kids to be curious, to cherry picking some handy examples from the past for them. The examples chosen paint a pretty clear picture of a nation that hasn’t changed enough in 400 years, and hasn’t changed at all since the Jim Crow era.

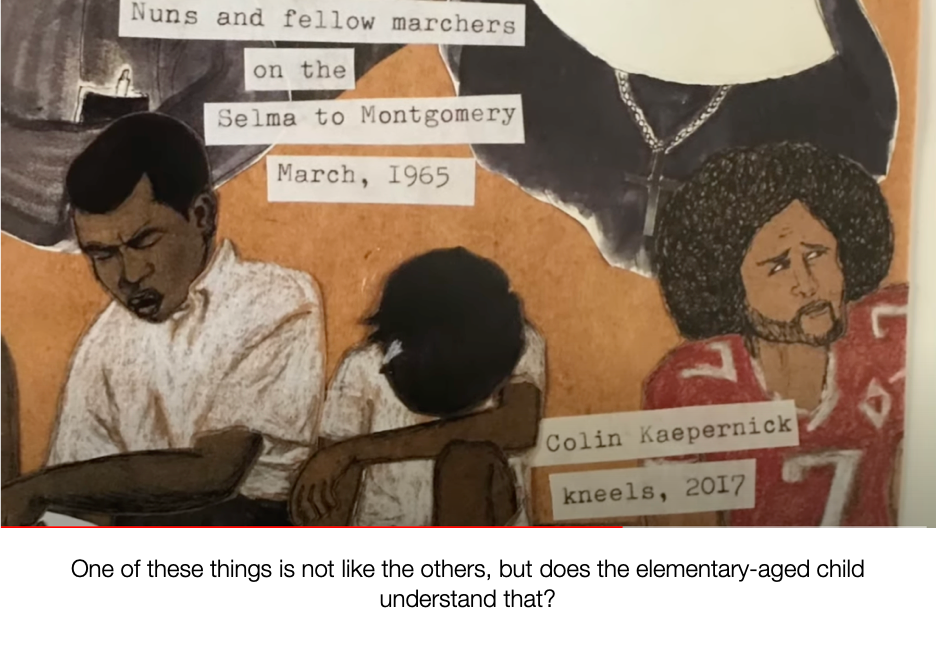

Take the image below for example, placing Civil Rights marchers, like John Lewis, kneeling in the 1960s next to Colin Kaepernick kneeling in 2017? What’s the point of this if not to make the child think not much has changed? Even a child who can’t do arithmetic yet can figure out a lot of time has passed between the two events, but are they as likely to recognize the absurdity of comparing people treated like second-class citizens with an NFL football player making millions of dollars? Probably not, especially when the very next page says “Racism is still happening; it keeps changing, and keeps being the same.”

Finally, the book tells the white child specifically the way to fight racism is to “open up,” to accept what the book is telling them as “true,” but warns them that “opening up sometimes feels like breaking.”

Why would teachers, or parents for that matter, be so eager to expose young children to information that might make them feel like they are “breaking?” How is feeling like you are personally in pain going to help other people? I’m unaware of any evidence that supports the idea that causing pain in young children makes them better people, but the author of the book, and the teachers teaching the book, obviously seem to think it does.

After the child in the book is told how it feels like “breaking” to accept the “truth,” we see her getting angry with her mother who’s driving the car. The child says she doesn’t feel well, and the mother offers to pull over, at which point the child demands to know “Why didn’t anyone teach me real history?”

This child is barely tall enough to see out the window of the car! Has she been taught any history yet?And what does she mean by “real history?” Inferring from the illustrations and messaging in this book, “real history” is any version teaching that “whiteness” is racism, racism is as bad today as it was during the Jim Crow era, it’s white people’s problem to fix, and all police shootings of black people are racially-motivated and wrong. I realize there are many people who agree with these statements, but that doesn’t make them “facts.” These are still opinions, and we don’t refer to opinions as “real history,” or teach them as facts to young children who are in no position to argue.

In my opinion, the author’s final point has the most potential to damage the reader/listener long-term: “Innocence is overrated; knowledge is power.”

An older child hearing or reading this could be challenged to agree or disagree, and to discuss the merits of the claim, but again, we are talking about children as young as the six year-olds targeted by the video above. Why would any teacher choose a book with this parting message? Since when is it the job of the school to decide that innocence is overrated for the children in their care? Is everything an adult knows appropriate for a child to know?

It’s a unique privilege to have access to the developing intellect and psyche of a child. Teachers and parents alike should be careful to avoid giving children the impression, never mind explicitly telling them, they are obligated to fix problems created by adults, or share the burden of negative emotions adults are feeling while they cope with those problems. Some would — I would — even classify the way this book insists on forcing children to see things through adult eyes, as abusive.

There is a time and stage of development for teaching, and learning about America’s past, especially the darker parts of it. I don’t say this out of any impulse to evade the truth, or to sugarcoat it, but rather to ensure students are ready, emotionally and intellectually, to question their teachers, and learn how to find “the truth,” so they’re never simply at the mercy of others to tell them what it is.

It goes without saying we are each entitled to our own opinion, and to form our own conclusions about racism; where it still exists, what form it takes, what we can and should each do about it, and what we would like our elected officials to do about it. It should also go without saying our children are entitled to do the same, at their own pace. When teachers try to skip ahead of the child’s developmental timetable, they are not teaching, they are indoctrinating, and all of us should do what we can to stop them.

"Innocence is underrated" is such a creepy line. Ugh. What a terrible book.

Excellent article, Deb. Thanks. 👏🏻

Good lord! Haven’t we learned ANYTHING from sexual abuse crises??? There’s no way a book with a line like “innocence is overrated” would get past a safeguarding officer in a Catholic school these days. Learn from our mistakes people!