Stop Blaming Women. The Real Problem In Our Schools Isn’t "Feminization."

A forgotten history reveals how we mistook institutional obedience for femininity and called the result a gender crisis.

I recently had an epiphany that embarrassed me, given how much work I have done exposing how far compulsory government education goes to undermine or even openly attack individualism. For years, I have argued that schools are deeply collectivist, even Marxian in spirit. Yet despite this, I found myself thoughtlessly repeating the phrase “schools are feminizing boys.”

I am embarrassed that I accepted and repeated that idea without examining it more carefully. Hidden inside that phrase are two incorrect assumptions. The first is the belief that traits like agreeableness, subservience, prioritizing the group over the individual, and excessive concern with authority and social approval are inherently feminine. The second is the belief that it is the school’s responsibility to ensure boys graduate with a standardized level of masculinity, as if there is a measurable target that every male child should reach, and any deviation from that target should be called “feminization.”

I should have known better.

This realization was especially uncomfortable because I was a tomboy growing up. I was energetic, not particularly agreeable, and socially awkward in ways many people describe as masculine. I was direct in my speech. I rarely added qualifiers to my questions. I did not smile unless I had a reason to. People told me “You would be so much prettier if you smiled more often” which implied that my unwillingness to perform pleasantness on command made me less likable and less feminine.

All my closest friends were boys. I was the only girl on the boys’ soccer team because our town did not offer a girls’ league, and I even wore clothes from the boys’ section. I did not succeed academically because I was compliant or eager to please. I succeeded because I was curious and determined. I know this is true because one of my teachers once told me I was not a “joy to have around when I am trying to cover material.”

I asked too many questions. I interrupted when I needed clarity. I struggled to sit still for long periods. I rarely conformed and always felt out of place. From the outside, looking only at my grades, no one would have seen any of this as a struggle.

My own story should have been enough to make me question the claim that schools benefit girls simply because the system has been “feminized.”

For years I heard people, especially conservatives, claim that boys are falling behind academically because education has been feminized. My epiphany began with a simple question I asked myself a few weeks ago: in what specific way does feminization benefit girls?

That question led to several others.

Why is it considered preferential treatment to reward traits labeled feminine while discouraging traits labeled masculine?

What benefit is there for girls to spend thirteen years in an institution that teaches them to succeed by ignoring their own needs, prioritizing external authority over internal knowledge, and subordinating personal ambition to group approval?

How does it help a girl to be trained to see compliance as virtue and self-abandonment as a prerequisite for belonging?

Searching for answers to these questions helped me realize I had made a serious conceptual mistake. Critics of the education system, myself included, had been treating individualism, boundary setting, and resistance as masculine, while treating subservience, agreeableness, and compliance as feminine. Then we added a second mistake by assuming girls benefit because these supposedly feminine traits are universal to all girls and women, and rewarded in school.

Once I saw it, I could not un-see it: the entire story about the “feminization” of education is backwards. Women did not design this system. Women did not take over schools. Women did not create an institution that privileges girls and handicaps boys. They were placed inside a machine they had almost no power to shape.

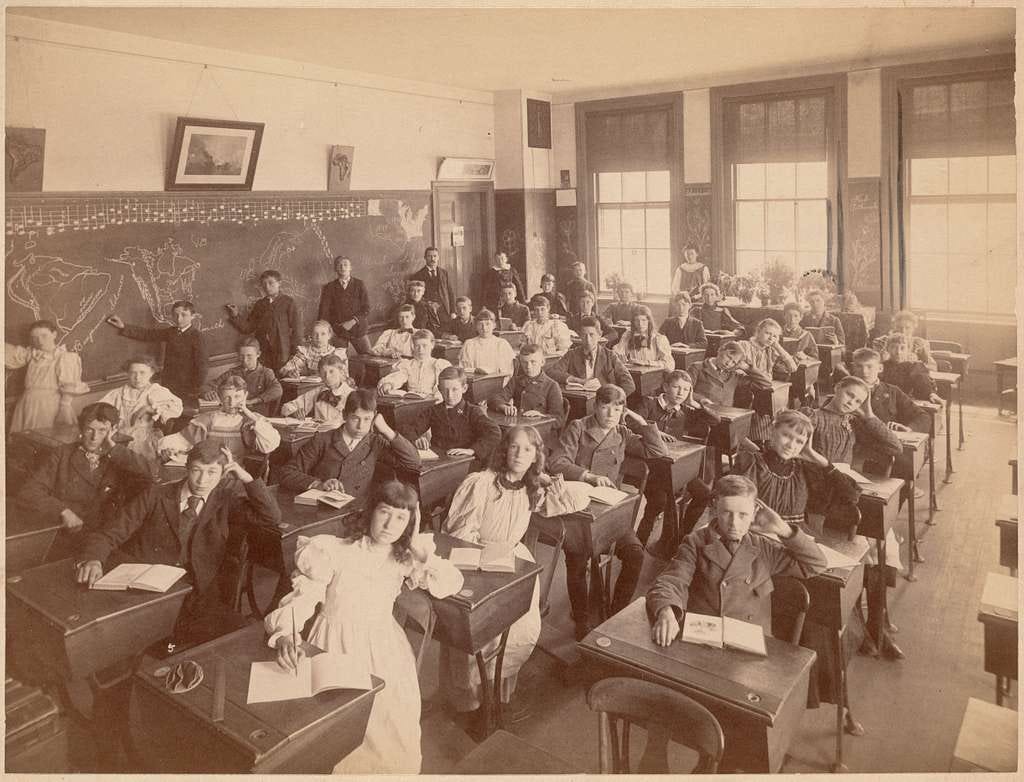

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the leadership of American public education consisted almost entirely of men. Legislators were men. School boards were men. Superintendents were men. The architects of compulsory schooling and the common-school movement were men. Every major structural decision came from these male-controlled institutions.

When compulsory schooling expanded, the United States faced an enormous teacher shortage. At the same time, American industry was exploding. Men could earn far more in factories, railroads, engineering, and construction than they could as teachers. Historical accounts show that men increasingly left the classroom for higher-paying industrial work. School boards reacted the way institutions always do when they need large amounts of labor for as little money as possible. They hired women.

The pay gap was enormous. Women were routinely paid half, or even less than half, of what men earned for the same work. This is documented in historical analyses of the common-school era, including the Country School Association’s research and MIT’s analysis of the feminization of teaching. Local governments openly discussed the financial savings of replacing male teachers with women. This was not a philosophical choice. It was a budgetary strategy.

Teacher-training programs, known as normal schools, were created to produce large numbers of teachers quickly. These programs recruited mostly women because women had so few socially acceptable career options, and teaching was one of the only professions considered respectable for them. Reformers like Horace Mann expanded these schools as part of his effort to standardize public education, and Catherine Beecher encouraged women to enter teaching because she believed they were a practical and available workforce who could stabilize the system during periods of severe shortage.

None of this was part of a feminist movement to redesign schools. Women did not have the political agency to overhaul institutions even if they had wanted to. They could not vote. They rarely held property without permission. Their legal autonomy was limited in nearly every dimension. They did not possess the authority required to restructure an entire national system.

By the early twentieth century, teaching had become one of the only respectable professions open to women. This was not because teaching uplifted women but because nearly every other professional path was closed to them. Men continued to control school budgets, policy, curriculum, and administration. Women filled the lowest-paid and least influential roles. The culture of the schools that developed — uniform behavior, obedience, quiet classrooms, predictable routines — grew out of bureaucratic necessity, not feminist activism. It came from the priorities of large systems, not the personal preferences of the women hired to staff them.

Once I understood this clearly, the entire narrative that women “feminized” schools fell apart. The system was never built to serve women. It was built to use them. And now, more than a century later, the same system is blamed on them as if they masterminded it. As if they had the political power in 1890 to feminize anything.

I want to be clear about something here. I am not pretending that feminism or other progressive movements never used the public schools to advance their political goals. Of course they did. Once the system existed and once the state poured money and authority into it, every political movement tried to shape curriculum, culture, and pedagogy to reflect its worldview. That is the nature of large institutions. What I am arguing is that blaming “women” as a category for the feminization of education is historically illiterate, wildly oversimplified, and obscures far more than it reveals. Most importantly, it distracts us from the real problem we should be fighting: the institutional culture of conformity, obedience, collectivism, and submission that harms all of us, regardless of sex or ideology.

At some point we have to stop repeating this error, because continuing to blame women is not analysis, it is complicity in the very system we claim to oppose. What people describe as “feminization” is not feminine. It is authoritarian collectivism engineering a convenient misunderstanding, ensuring that men blame women instead of confronting the system that is harming their children.

In general, I think that labelling the phenomenon "feminization" is just probably unnecessarily polemical, and in the end doesn't even really help describe concretely what it is that is happening. Like, I get what they mean, but it can be explained more clearly, and with less of the culture-war baggage, if they just focus on the actual effects, and less on the gendered blame game.

Thank you for this. I agree with much of what you say, However, while there are definitely similarities, the way in which schools have been "feminised" in the UK is slightly different, and I can see the hand of majority female educators (teachers and planners) in this, in recent decades. For example, the replacement of exams with course work, which most girls apparently prefer; the content of curricula moving too often from objective facts to "lived experience"; and a growing misunderstanding of how boys fail to thrive if they have to sit still for long periods of time (although I accept what you say about bureaucratic necessity). Of course these are generalisations, and I – like you – was not a typical girl. Having worked in schools though, I can see how the current direction of travel benefits girls and young women, and fails to inspire and motivate young men.