I want to dig into the topic of “socialization” brought up today on X (see post below from Homeschool_LLC) because I truly believe the enduring myth he describes is likely the primary reason most people who could and would be inclined to homeschool their children, choose not to. “What about Socialization” was, and still is, the most common question I get, often followed by “but aren’t you afraid they’ll be weird?”

The following details what I now say to people who ask this question. Feel free to use it yourself or, if you’re one of the people inclined to ask the question, please read this with an open mind.

Define “weird?”

Hey, this is me. If you don’t know already, you soon will; I am a person who insists that people define their terms before I will engage in any discussion, least of all one aimed at (unsolicited) denigration or judgement of my life choices.

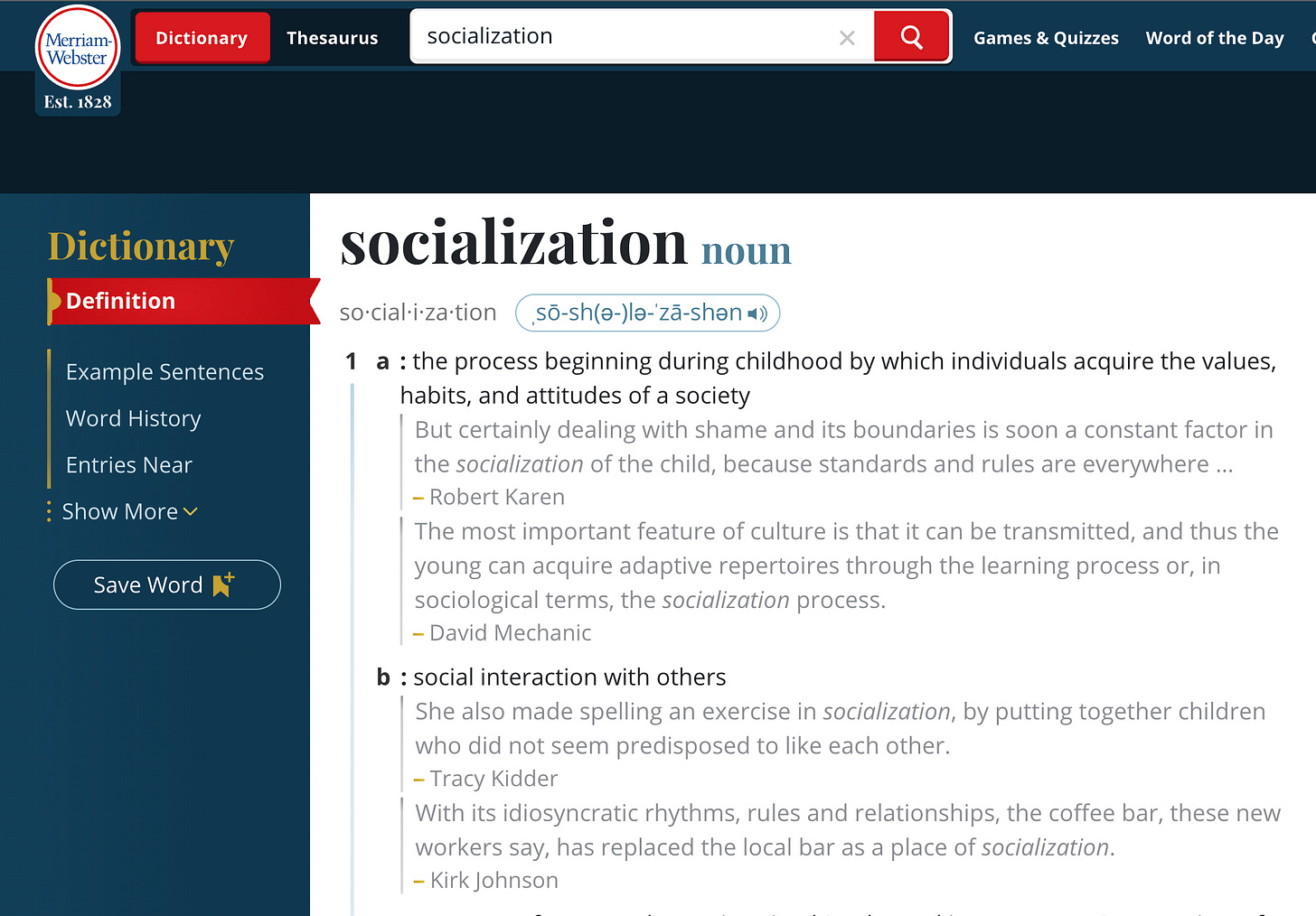

Here’s what the dictionary says:

Well look at that: “Of strange or extraordinary character: ODD, FANTASTIC.” That would only be a bad thing if the opposite of weird is universally desirable, right? Well what are the antonyms for “weird?”

Hmmm…I don’t know about y’all, but I’m not aiming to raise a “typical” adult, or an “ordinary” one either. I’m not saying I’ll be disappointed in my kids if they aren’t stand-outs in some way, but I want them to be individuals, not conformists, especially if I don’t approve of the “commonplace” “standards” that are “usual” in today’s society.

Still, I doubt most people using the term mean “weird” exclusively the way it’s defined above. My guess is they mean “Won’t know how to get along or interact with people,” or “Won’t know how to make friends.” So that brings me to my next point:

What does “getting along with” others look like?

There are two interpretations of the phrase “getting along with.” I’m not using the dictionary now, I’m defining these based on my own experience, and answers given to me by anti-homeschoolers when I’ve asked them:

Able to interact with people who disagree, or are not like them, without experiencing unmanageable1 distress or conflict, and while still maintaining their own personal boundaries (that is, behaving in polite, respectful, situationally-appropriate ways, without sacrificing their own needs, or abandoning their own values).

Conforming to the behavior of the dominant personalities in any given space, or subjugating their own needs and values to the demands and desires of the collective.

OK, to be fair, no one actually gave me that second definition as-written, I’m extrapolating from comments like “C’mon, you know what I mean!” and “Not standing out, not being a creepy loner…Doing what the other kids are doing, you know, having an active social life with friends!”

Most people would probably agree that answer number one makes sense, and is probably what most parents think “getting along with” others ought to look like, so then the question is, are homeschoolers really hobbled in their ability to “get along” with others by that definition? No, they are not, and research backs me up on this. Kerry McDonald reported in February of this year that research done by the Harvard Human Flourishing Program found:

“…home-schooled children generally develop into well-adjusted, responsible and socially engaged young adults,”

So then the next logical question should be,

How are kids “socialized” at school?

Homeschoolers like me don’t dispute the fact that schools do “socialize” kids, we just dispute that they do it better than homeschooling. We say that because our definition of “good” includes “getting along with others” as described above. Therefore to be objectively “better” at socialization, schools would have to produce people who get along “better” by those standards than people who are homeschooled.

Look around; Is it your experience that the average public school kid “gets along better” with people? Are they more respectful towards their teachers, parents, and strangers in public? Do they get into fewer fights with their peers, or express less rage or extreme disappointment when they don’t get what they want? When they meet new people, are they more comfortable making eye-contact, introducing themselves, and starting conversations than their homeschooled peers?

Evidence would strongly suggest they don’t. One in six school-aged children is suffering with some form of mental illness. School attendance alone is strongly correlated with youth suicide, and especially since the lockdowns, school violence has gone up steadily year after year.

Are these statistics that argue for school-based socialization? Even if you don’t blame the school, or its approach to setting and enforcing standards of behavior, for all that dysfunction, you can’t deny that telling families their kids will be “weird” if they don’t go to school isn’t a compelling argument against homeschooling. Even if “weird” did mean friendless and awkward, is that really worse than suicidally depressed and violent, or in classes all day with kids who are?

Now unlike some homeschooling parents, I’m not going to sit here and pretend that all homeschoolers are better socialized than all school kids. Personality, parenting, and other factors influence how children get along with other people. I’m just making the case that “socialization” at school isn’t automatically better, and might actually be worse.

Socialization vs. Socializing

Socializing and socialization often get confused, but as much as the latter may be part of the former, they are different in important ways.

School may provide more opportunities to children for “social interaction” with other children, but if the state told you tomorrow that your social circle would be defined by your age and zip code, would you be grateful, or looking for a way out?

Also remember your child isn’t going to school to socialize, but to learn all the things they’ll need to know to make some pretty major decisions about the rest of their lives. Should they go to college, or pursue a trade? Should they become an entrepreneur, or be an employee? What kind of person do they want to be when they grow up? We expect our kids to make choices by the end of their senior year in High School that will shape the rest of their lives, but we often forget that “socialization” will play a major role in how they make those choices.

Sure, it’s nice to be able to make some friends along the way, especially if you’re stuck in a building all day for nine months, but why do we even accept that arrangement as a “normal” childhood?” If socialization is supposed to teach children the “values, habits, and attitudes” of a society, wouldn’t it be more realistic to expose children to a wider variety of people and experiences, as homeschooling families do? After all, “homeschooling” doesn’t literally mean “confined to home” the way “schooling” means “confined to school.”

Not all “values, habits, and attitudes” are equal

Finally, my answer to the “What about socialization” question would be incomplete without reference to the nature of the “values, habits, and attitudes” schools today want to “socialize” into our children. Social Emotional Learning (SEL) programs most (if not all) American schools use today teach that “Social Justice” the highest value. To achieve it, they teach kids to develop a habit of “identifying” themselves and others by immutable characteristics like race, ethnicity, sex, religion, and socioeconomic class, and encourage them to adopt the attitude that the society, in America especially, is so unjust, it must be completely “deconstructed.”

What that means is, far from teaching our children how to “get along with others,” it’s teaching them how to identify what’s wrong with themselves, or others, so they can become “change agents.”

Gone are the days when Americans could count on schools reenforcing the values, habits, and attitudes of a shared culture. Now the mere mention of a “shared culture” can spark outrage in an SEL educator, who will tell you it’s more important for our children to be socially aware, and culturally-responsive, so they can avoid cultural-appropriation, or micro-aggressing against others. As a consequence, school-based socialization makes social interaction more like navigating an interpersonal minefield of potential hurt-feelings and perceived injustice. Is it any wonder anxiety levels are so high?

Socialization is WHY we homeschool

Socialization is important, there’s no question about it, but the perception that it doesn’t happen, or can’t happen, or can’t happen “properly” outside of schools, is false. Socialization happens whether we like it or not. Human beings who aren’t living as hermits in the woods, literally tucked away from all other humans, interact with other humans inside their own homes, and every time they go out, no matter where they go. Children watch the people around them, how they start and end conversations, how they speak to each other, how they handle disappointment and conflict involving other people, and how they make friends.

Homeschooling families know all this, and it’s one of the main reasons we homeschool. Why shouldn’t we be the ones to teach our children values, habits, and attitudes they’ll need to succeed in society? If you think about it, if we’re not qualified to do that, we’re not qualified to parent them in the first place.

Learn more

More about socialization:

SEL Defined below, and here’s my playlist of my own work about SEL.

Unmanageable in the sense that they’d need an adult to intervene to calm them down, or prevent escalation to violence.